Hydrogen atoms sandwiched by fluorine exhibited the quirk of chemistry

Students of chemistry around the globe are familiar with covalent and hydrogen bonding. Now, a study has uncovered an unusual relationship that resembles a hybrid of the two. Its features raise problems regarding the definition of chemical bonds, researchers say in Science on January 8.

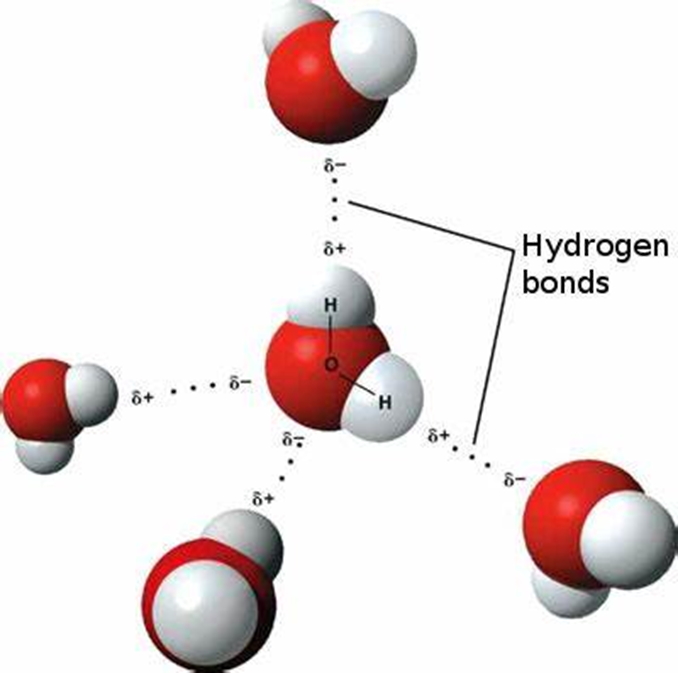

Hydrogen bonds are often viewed as weak electrical attractions as opposed to genuine chemical connections. Covalent bonds, on the other hand, are strong chemical connections that hold atoms in a molecule together and come from the sharing of electrons between atoms. Now, scientists discover that an extraordinarily strong type of hydrogen bond is actually a hybrid because it involves shared electrons, blurring the line between hydrogen and covalent connections.

According to University of Chicago scientist Andrei Tokmakoff, our concept of chemical bonding, as well as the way we teach it, is extremely binary. The latest study demonstrates that “there is in fact a continuum.”

Tokmakoff and coworkers characterized the hybrid bond by examining bifluoride ions in water, which consist of a single hydrogen atom sandwiched between two fluorine atoms. According to popular wisdom, the hydrogen atom is covalently bonded to one fluorine and hydrogen-bonded to the other.

Using infrared light, the researchers caused bifluoride ions to oscillate and then analyzed the hydrogen atoms’ response, revealing a range of energy levels at which the hydrogen atoms vibrated. As an atom ascends the energy ladder, the distance between these energy levels decreases for a normal hydrogen connection. However, the researchers discovered an increase in spacing. This behavior suggested that the hydrogen atom was shared evenly between the two fluorine atoms, as opposed to being tightly attached to one fluorine atom by a covalent bond and weakly bound to the other by a normal hydrogen bond. In this configuration, co-author Bogdan Dereka, a chemist at the University of Chicago, explains, “the distinction between the covalent and [hydrogen] bonds is obliterated and becomes meaningless.”

This behavior is based on the distance between the two fluorine atoms, as calculated by a computer. As the fluorine atoms move closer together, squeezing the hydrogen between them, the usual hydrogen bond strengthens until all three atoms begin exchanging electrons as in a covalent bond, establishing a single link that the researchers refer to as a hydrogen-mediated chemical bond. The typical model with discrete covalent and hydrogen bonds still applies to fluorine atoms that are further away.

The researchers conclude that the hydrogen-mediated chemical bond cannot be defined as either a pure hydrogen bond or a pure covalent bond. Mischa Bonn, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz, Germany, and co-author of a Science perspective piece on the discovery, describes it as a mixture of the two.

Hydrogen bonds exist in numerous substances, most notably in water. Without hydrogen bonding, water would be a gas at normal temperature rather than a liquid. While the majority of hydrogen bonds in water are weak, water with an abundance of hydrogen ions can form strong hydrogen bonds similar to those found in bifluoride ions. Two water molecules can sandwich a hydrogen ion to form what is known as a Zundel ion, in which the hydrogen ion is shared evenly by both water molecules. The latest findings mirror the behavior of the Zundel ion, according to chemist Erik Nibbering of the Max Born Institute for Nonlinear Optics and Short Pulse Spectroscopy in Berlin, who coauthored a 2017 Science study on the ion. It everything goes together well.

It is believed that strong hydrogen bonds play a role in the movement of hydrogen ions, a process that is essential for a range of biological activities, including cellular energy production and technology such as fuel cells. Consequently, a deeper comprehension of these linkages could shed light on a number of outcomes.

And the new observation has consequences for how scientists comprehend fundamental chemical concepts. It relates to our fundamental knowledge of what a chemical connection is, according to Bonn.

This newly acquired knowledge of chemical bonding raises problems regarding what constitutes a molecule. Atoms linked by covalent bonds are believed to be part of a single molecule, whereas those linked by hydrogen bonds can exist as independent entities. Therefore, bonds in limbo between the two beg the issue, “When does one molecule become two?”